|

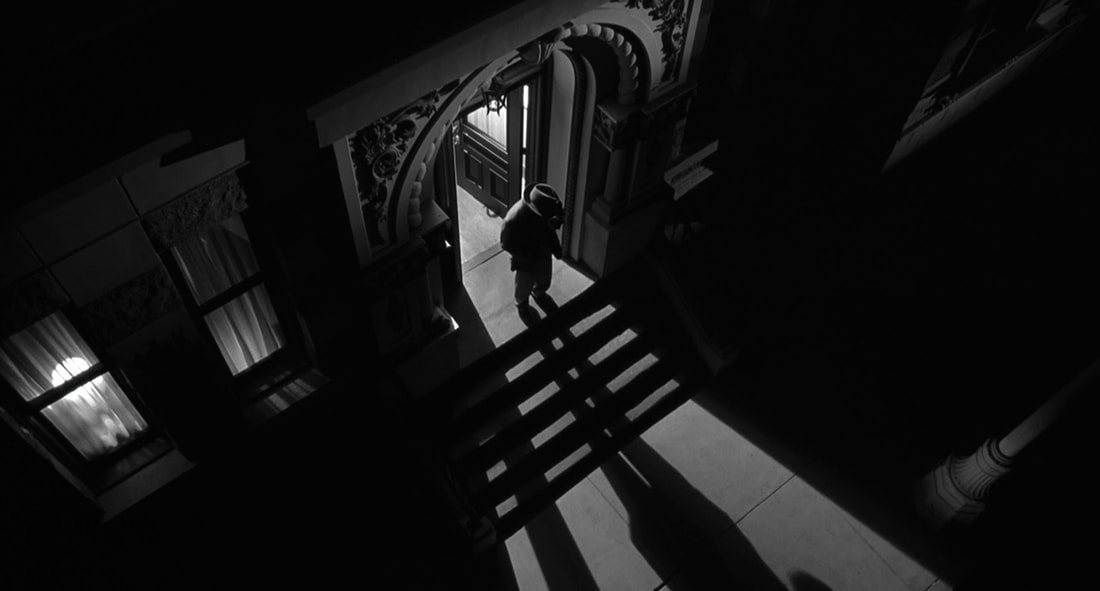

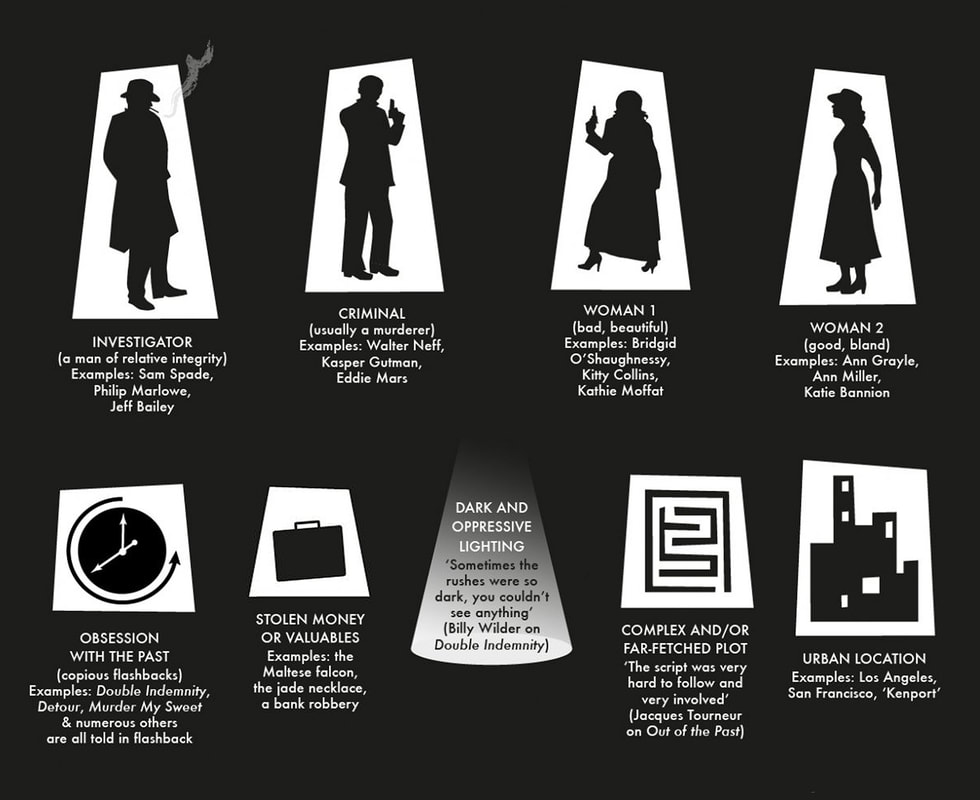

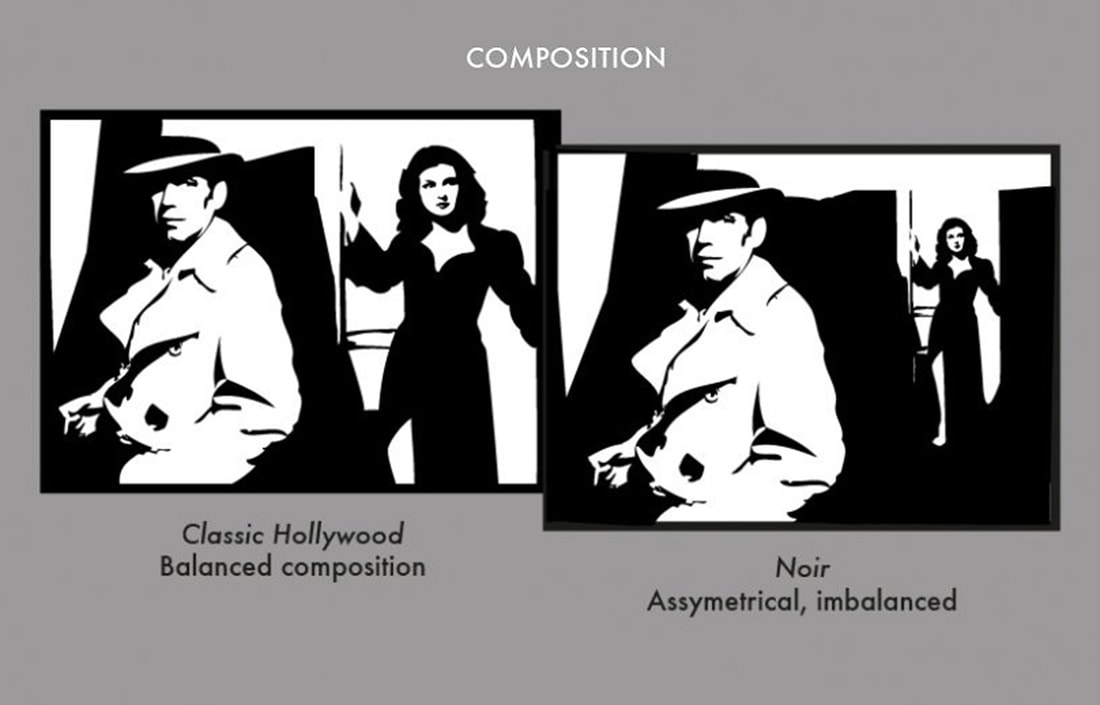

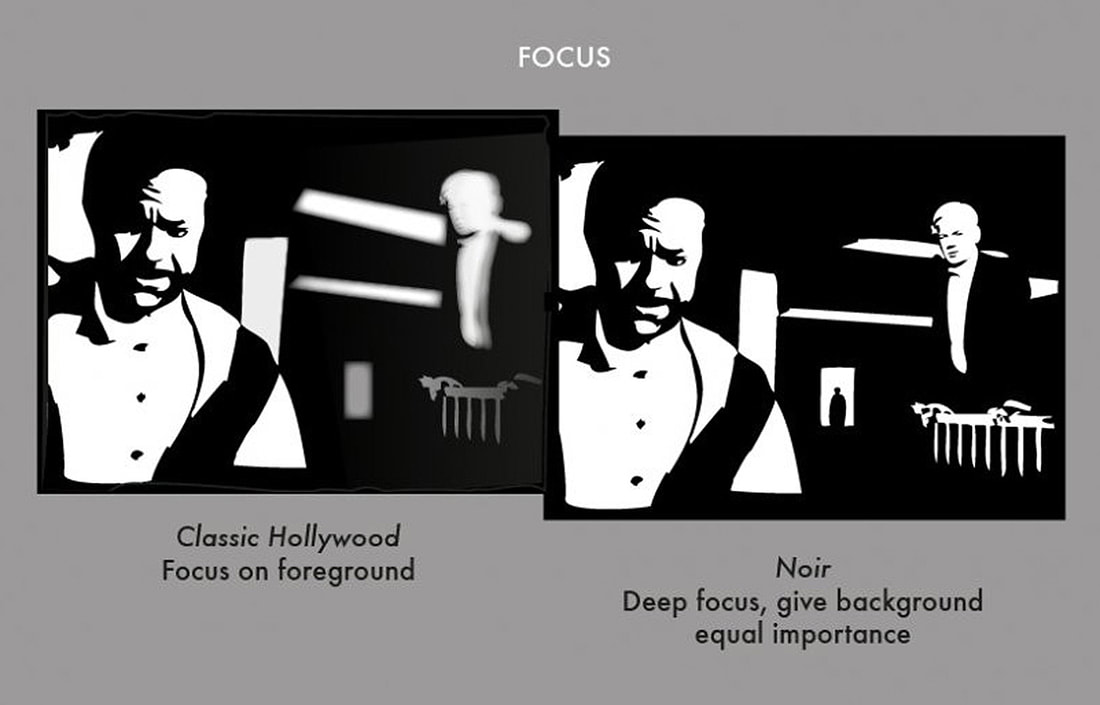

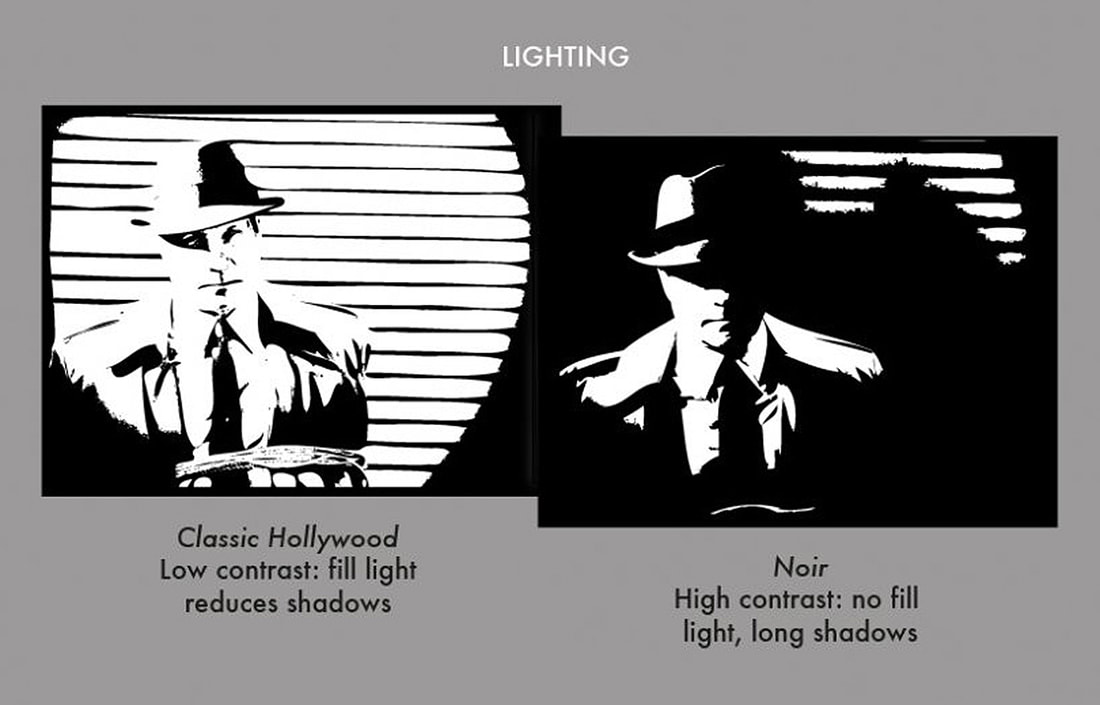

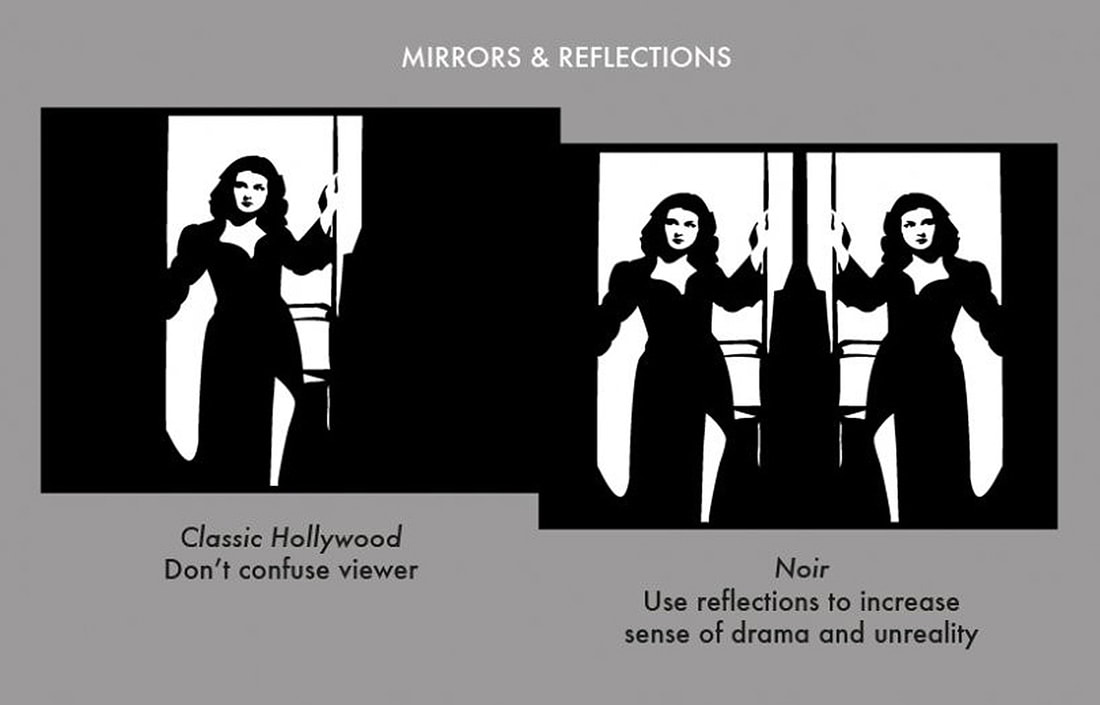

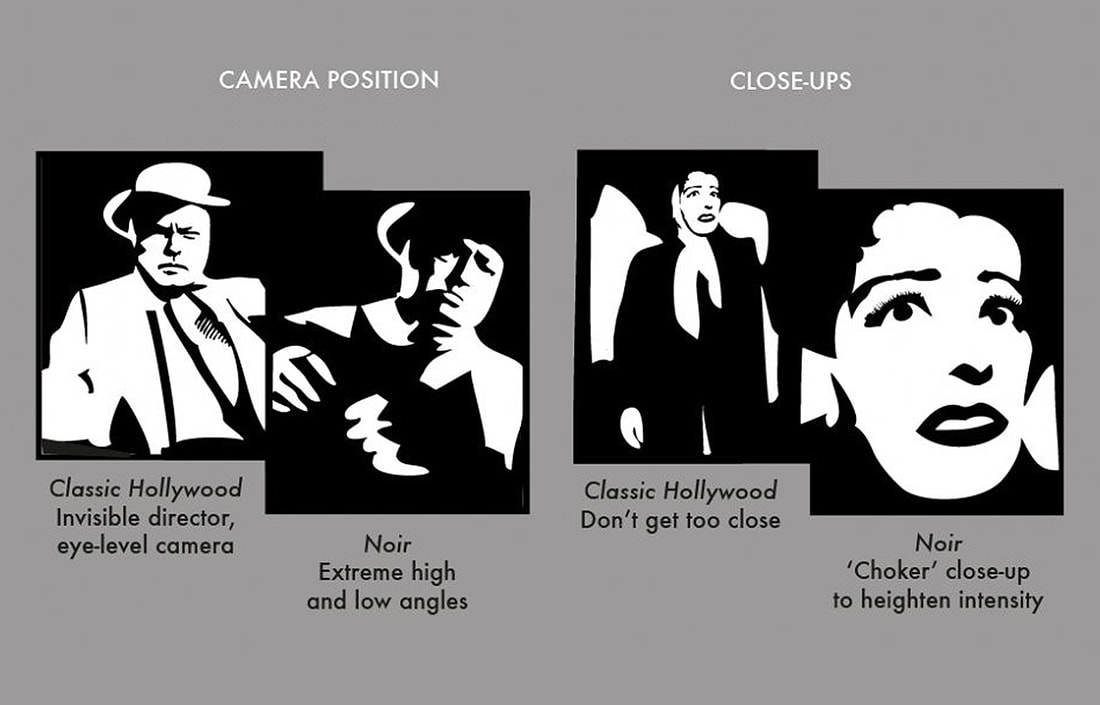

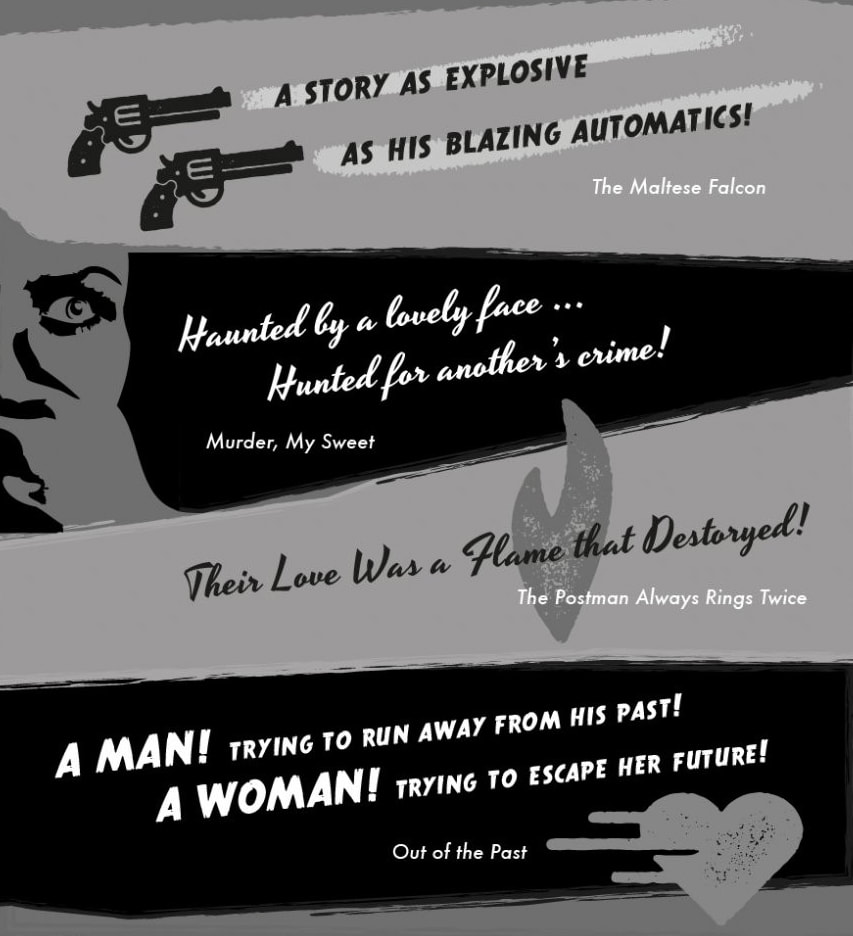

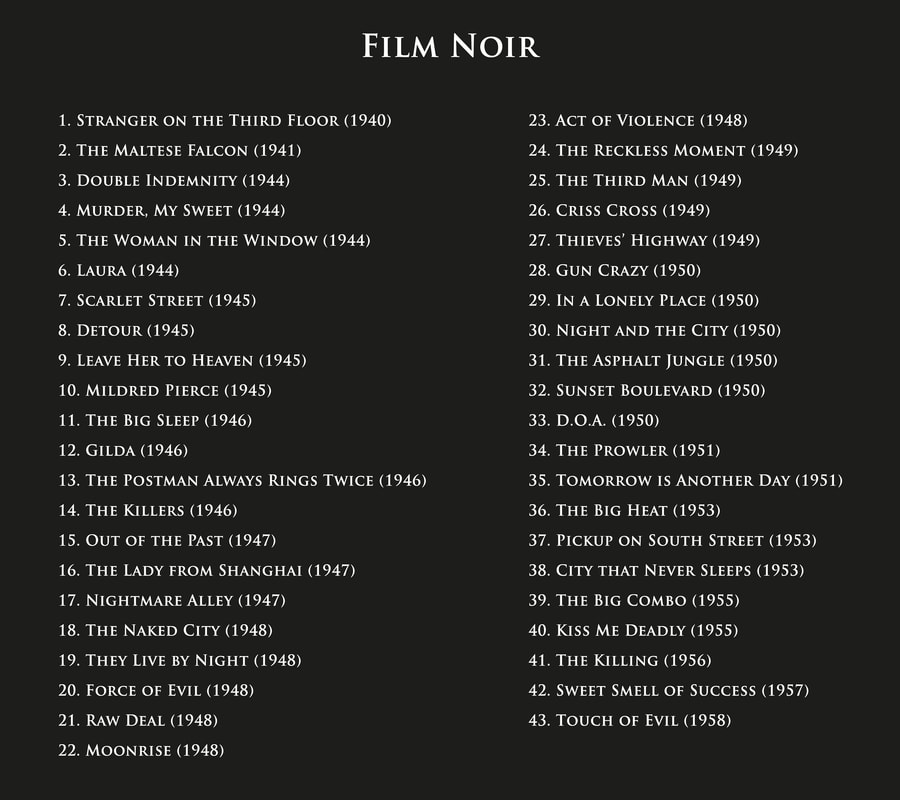

“We didn’t’ exactly believe your story, Miss O’Shaughnessy. We believed your two hundred dollars. I mean, you paid us more than if you’d been telling the truth, and enough more to make it all right.” -Sam Spade, 1941 From lighting and shadows to crime dramas and femme fatales, there are several elements that come together to shape a film noir. The term itself, French for “dark film,” was first coined by French critic Nino Frank in 1946 to refer to the distinctive black and white aesthetic. Before the idea was widely accepted in the 1970s, however, many of the classic film noirs were simply referred to as melodramas. Embracing a wide variety of genres, from the gangster film and police procedural to the gothic romance and social problem picture, a strict categorization of film noir has remained elusive and continues to provoke debate. However, there are fundamental components of film noir that remain consistent throughout its impressive repertoire. The unique visual style of film noir is generally associated with low-key lighting and an unbalanced composition that has its roots in German expressionist cinematography. These films dealt with a multitude of psychological tropes that were both timeless as well as distinct to the era. Many of the prototypical stories of classic noir are derived from the hardboiled school of crime fiction that emerged in the U.S. during the Great Depression. Hollywood’s classical film noir period stretches from the early 1940s to the late 1950s, with the first ‘true’ film noir generally considered to be 1940’s Stranger on the Third Floor. The films are often associated with an urban setting, with cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago serving as prominent locales. In the eyes of many critics, the city is presented as a labyrinth or maze that the protagonists need to navigate before unraveling the underlying scheme. The climaxes of a substantial number of noirs takes place in visually complex, often industrial settings, such as refineries, factories, trainyards, and power plants.  However, many classic noirs take place in small towns, rural areas, suburbia, or even on the open road. Similarly, while the private eye investigator and the femme fatale are recurring character types conventionally identified with noir, many films feature neither. Crime, usually murder, is an element found in almost all film noirs. In addition to standard-issue greed, jealousy is frequently the criminal motivation. In other common plots, the protagonists are implicated in heists or con games, or in murderous conspiracies often involving false suspicions and betrayals. Most film noirs of the classic period relied on a modest budget and did not feature major stars. In this regard, writers, directors, and cinematographers were relatively free from the typical big-picture constraints. This freedom lead to much of the visual experimentation that took place during those years. Narrative structures sometimes involved convoluted flashbacks that were uncommon in the typical commercial production. Enforcement of the Production Code, however, ensured that no film character could get away with murder on screen, or be seen sharing a bed with anyone but a spouse. Nonetheless, within those bounds, many noirs featured plot elements and dialogue that were very risqué for the time. Perhaps the epitome of the genre is found in Billy Wilder’s 1944 classic Double Indemnity. The film’s commercial success and seven Academy Award nominations made it the most influential of the early noirs. Barbara Stanwyck’s unforgettable femme fatale inspired a slew of notable performances, from Rita Hayworth in Gilda (1946) and Lana Turner in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) to Ava Gardner in The Killers (1946) and Jane Greer in Out of the Past (1947). The latter film in particular featured many of the genre’s hallmarks: a cynical private detective, a femme fatale, multiple flashbacks with voiceover narration, dramatically shadowed photography, and a fatalistic mood leavened with provocative banter. The iconic noir counterpart to the femme fatale, the private investigator, came to the fore in films like The Maltese Falcon (1941), with Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, and Murder, My Sweet (1944), with Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe. Generally considered one of the last examples of the genre’s classic era, Touch of Evil (1958) features many of the same attributes that made its predecessors tick. Orson Welles’s baroquely styled film is often cited as one of his best motion pictures. The exceptional cinematography was used to add depth to the complex plot by showing interpersonal connections and “trapping” the characters in the shame shots. The stark light and dark contrasts and dramatic shadow patterning was a style known as chiaroscuro, a term adopted from Renaissance painting. The shadows of Venetian blinds or banister rods, cast upon an actor, a wall, or an entire set, are an iconic visual in noir. Characters’ faces may be partially or wholly obscured by darkness, a relative rarity in conventional Hollywood filmmaking. Film noir is also known for its use of low-angle, wide-angle, and Dutch angle shots. Other devices of disorientation include shots of people reflected in one or more mirrors and shots through curved or frosted glass or other distorting objects. Night-for-night shooting, as opposed to the Hollywood norm of day-for-night, was also often employed. A stylish poster with a striking tagline was a common theme among the art of Film noir. It had a bold look and a unique iconography during its golden age. Studios commissioned arresting illustrations for even their lowest-budget thrillers. Many motion pictures released since that time have shared attributes with classic film noirs and often treat its conventions self-referentially. This has led some critics to dub them as neo-noirs. Developing mid-way into the Cold War, the trend reflected much of the cynicism and the possibility of nuclear annihilation of the era. The most acclaimed of the neo-noirs of the era is perhaps 1974’s Chinatown, set in 1930s Los Angeles and starring Jack Nicholson. Martin Scorsese’s seminal work, Taxi Driver (1976), on the other hand, brought the noir style crashing into the present day; featuring a crackling, bloody-minded gloss on bicentennial America. The state of New York City at the time was memorialized in the works of auteurs like Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola. From Mean Streets (1973) and the aforementioned Taxi Driver (1976) to The Godfather (1972) and Apocalypse Now (1979), they captured the nation going through a dark time, struggling to recuperate from a decade of war, political turmoil, and social revolution.  There have been several works that have strived to examine and analyze film noir over the years. Foster Hirsch’s The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir (1981), Alain Silver’s The Noir Style (1999) and Eddie Muller’s Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir (1998) are excellent resources. Hirsch’s book in particular offers a definitive study of the style, covering over one hundred films and offering more than two hundred carefully chosen stills. It is by far the most thorough and entertaining study available for noir themes, visual motifs, character types, actors, and directors. A few superb documentaries have also aired over the years with PBS’s American Cinema: Film Noir (1995), Film Noir: Bringing Darkness to Light (2006), and BBC’s The Rules of Film Noir (2009) being notable standouts. Below is a list of some of the most notable films from the style’s comprehensive repertoire. Film noir remains one of the most alluring and visually striking digressions of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Most noir stories told of people trapped in unwanted situations, striving against random, uncaring fate, and frequently doomed to tragedy. The films depict a world that is inherently corrupt; perhaps a commentary on the American social landscape of the era. It personified a sense of heightened anxiety and alienation that is said to have followed the events of World War II. As author Nicholas Christopher put it, “it is as if the war, and the social eruptions in its aftermath, unleashed demons that had been bottled up in the national psyche.”

3 Comments

Mohammad Osman

4/21/2021 01:12:24 pm

Thank you so much Katie :)! Glad you enjoyed it. I've always found Film Noir to be quite fascinating.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMohammad Osman is an Artist, Writer, & Cultural Historian. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Articles

-

Film

>

- Dark Side of the Screen: The Art of Film Noir

- Gothic Romance: The Art of the Macabre

- Perchance to Dream: The Art of Dark Deco

- The Road Goes Ever On: The Art of Middle-Earth

- There and Back Again: The Visual Poetry of Middle-earth

- King Kong: The Eighth Wonder of the World

- It's Alive: Universal Classic Monsters

- It Came from Beyond: Invasion of the Sci-Fi Films

- Creatures of Habit: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

- Myth and Magic: The Art of Comic Book Films

- Arabian Nights: Sinbad's Adventures

- Music >

- Games >

- History >

-

Film

>

- Artwork

- Community

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed