|

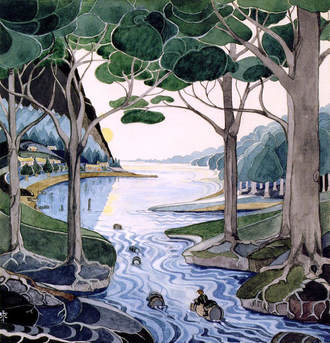

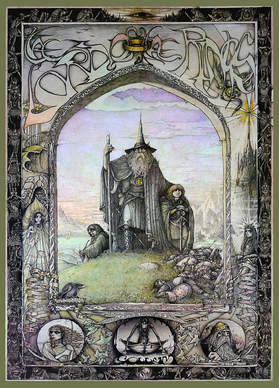

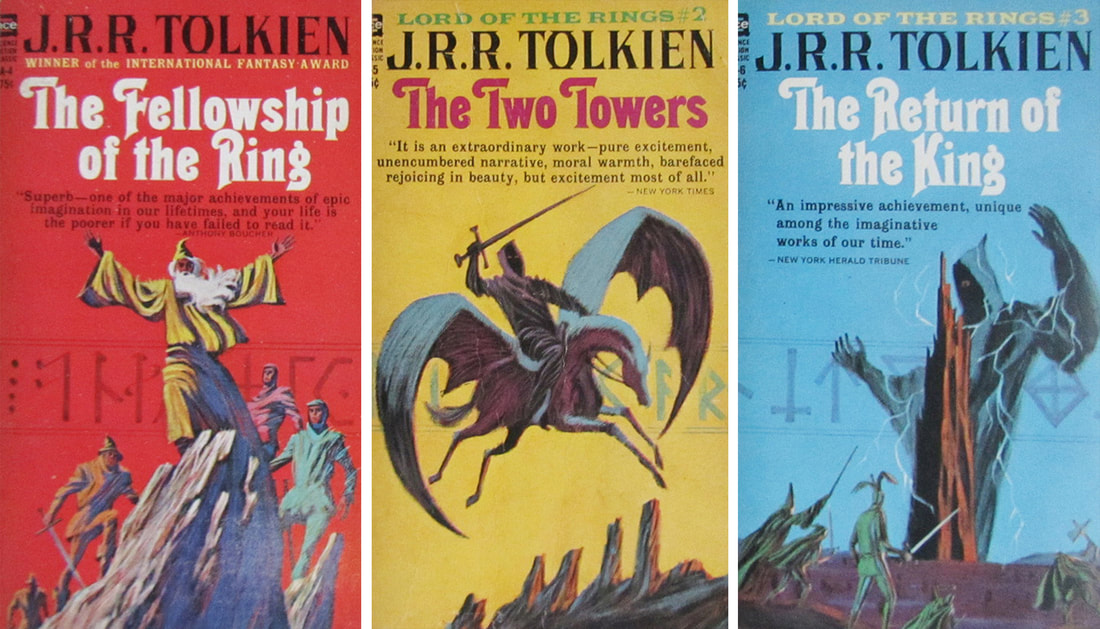

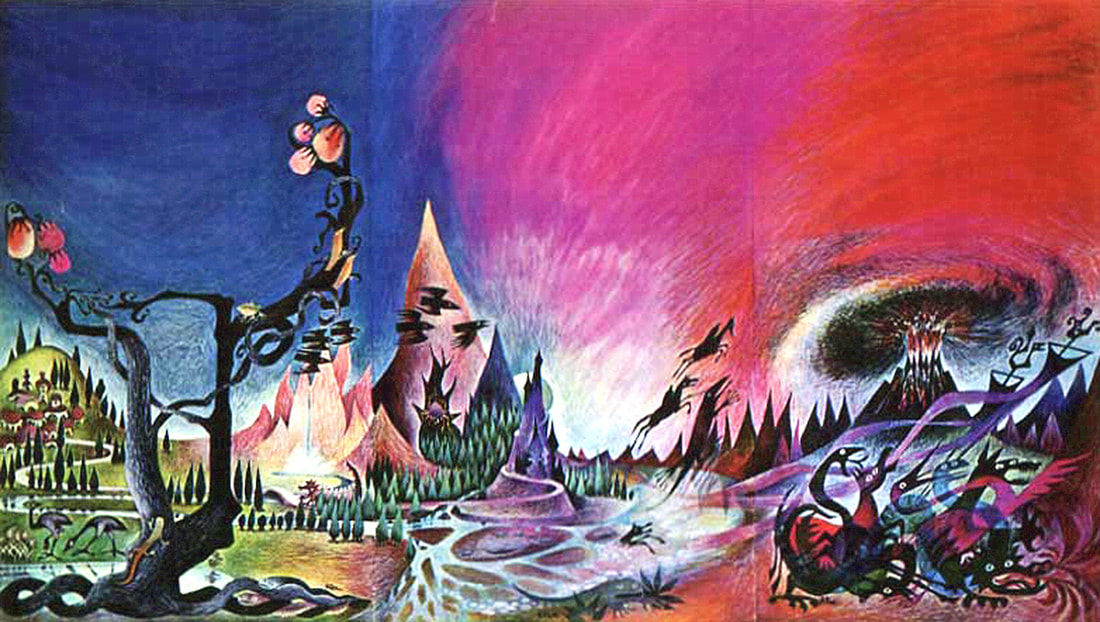

"The world is changed. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth. I smell it in the air. Much that once was is lost; for none now live who remember it. It began with the forging of the great rings: three were given to the Elves, immortal, wisest and fairest of all beings. Seven to the Dwarf Lords; great miners and craftsman of the mountain halls. And nine, nine rings were gifted to the race of men, who above all else desire power. For within these rings was bound the strength and will to govern each race. But they were all of them deceived, for another ring was made. In the land of Mordor, in the fires of Mount Doom, the dark lord Sauron forged, in secret, a master ring to control all others. And into this ring he poured his cruelty, his malice, and his will to dominate all life. One ring to rule them all." -Galadriel, 2001  Figure 1 Joseph Madlener's Der Berggeist (1925). Figure 1 Joseph Madlener's Der Berggeist (1925). Few names in the realm of high fantasy evoke more devotion and enthusiasm than J. R. R. Tolkien. While many authors had published works of fantasy before Tolkien, the immense success and popularity of The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-55) directly led to a popular resurgence of the genre. Although Tolkien’s fascinating characters and locations are ultimately confined to the readers’ imaginations, many artists and filmmakers over the past eight decades have attempted to bring his works to life. From still paintings and animation to live-action and musical numbers, the various ways in which Middle-earth has been brought to life over the years have each had their own unique flavor. Collectively, these diverse and distinctive interpretations add to the richness of the mythology and contribute to the ever-expanding pantheon of the art of Middle-earth. In the late 1920s, Tolkien had come across an interesting postcard depicting an old man sitting on a rock beneath a pine tree. With a long white beard, wide-brimmed hat, and a long cloak, the figure would go on to inspire the creation of Gandalf the Grey. Enamored by the artwork, Tolkien preserved the postcard and, years later, wrote on the cover: “Origin of Gandalf.” The art in question was a reproduction of Der Berggeist (1925), which translates as “The Mountain Spirit,” by German artist Joseph Madlener. In the painting, the old man is seen interacting with a young white fawn, with a humorous but compassionate expression. In the distance, behind the forest, a range of rocky mountains can be seen.  Figure 2 Tolkien's watercolor illustration "Bilbo Comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves" (1937). Figure 2 Tolkien's watercolor illustration "Bilbo Comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves" (1937). Following the success of The Hobbit (1937), Tolkien embarked on a sequel to his adventure, a project that would grow in scale and scope as the years passed by. The Lord of the Rings (1954-55) was eventually broken up into three individual volumes: The Fellowship of the Ring (1954), The Two Towers (1954), and The Return of the King (1955). It was published in England by George Allen & Unwin and imported to the U.S. by Houghton Mifflin. Perhaps the first piece of artwork created based on Tolkien’s work was by none other than the author himself. Ranging from rough sketches to full water color illustrations, Tolkien attempted to visualize what some of his key locations and structures looked like. Besides a few sketches of Bilbo, Gandalf, and the dwarves, however, we don’t get much insight into how Tolkien envisioned some of his other characters like Aragorn or Sméagol. A wonderful set of books by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull were published a few years ago, collecting all of Tolkien’s artwork based on his two seminal works. The Art of the Hobbit (2012) and The Art of the Lord of the Rings (2015) offer a treasure trove of sketches and illustrations that shed light on how Tolkien developed some of his iconic locations and architectures. While the books were successful in the U.K., however, no U.S. publisher had actually acquired the rights to print the books. In 1964, American publisher Donald Wallheim contacted Tolkien in earnest, regarding the possibility of acquiring the publishing rights for Ace Books, his publishing company. Tolkien was not interested in seeing his books appearing in paperback form, however, referring to the medium as “degenerate a form.” With some research, Wollheim found what he thought was a loophole in the copyright law for the books. The limited copyright Houghton Mifflin had been publishing under had expired and wasn’t renewed. Therefore, Wollheim assumed that the copyright for the books was now in the public domain. With this in mind, Wollheim set about publishing the first ever (unauthorized) paperback versions in the United States in 1965, with a new typeset and photographically reprinted appendices, a move that would prove to be both popular and highly controversial. Funnily enough, the illustrations used for the covers had very little resemblance to the actual characters or narrative of the story. Illustrated by Ace cover artist Jack Gaughan, the old man clad in a blue robe on the first book cover appears be a reference to Gandalf the Grey. The dark rider mounted on a winged-horse is assumed to be a depiction of a Nazgul, while the towering figure depicted on the third cover is presumably Sauron, with his blazing red eye. Aware of the looming copyright problems, Tolkien and Houghton Mifflin eventually published their own paperback versions of the books in late 1965 through Ballantine Books. Ironically, while Tolkien was displeased with the Ace editions, atleast their cover art portrayed illustrations that resembled the story. The Ballantine editions, on the other hand, sported a fantastical illustration by Barbara Remington that bore no resemblance to the plot of the books, lest for a fiery mountain in the background. Tolkien was understandably bewildered: “What has it got to do with the story? Where is this place? Why emus? And what is the thing in the foreground with pink bulbs?” It’s safe to assume that Remington’s artwork was atleast partially inspired by the psychedelic movement of the time period. It was around this time that social activists in the U.S. were beginning to hold Tolkien and his books in high esteem, as role models for how to live a peaceful life in tune with nature. Artists like Led Zeppelin incorporated familiar characters and locations into some of their songs like “The Battle of Evermore,” “Misty Mountain Hop,” and “Ramble On.” Around this time, there were a few artists who were inspired to create illustrations for Tolkien’s works. One of the earliest was Pauline Baynes, who had been commissioned by Tolkien to provide the cover art for the 1961 Puffin edition of The Hobbit. Notably, in a 1964 letter, Tolkien had described Baynes’ illustrations as “akin to my own inspiration.” She would go on to illustrate two map posters, including the Map of Middle-earth in 1970, as well as an illustration for Bilbo’s Last Song after the author’s passing. Another notable illustrator was Mary Fairburn, who created roughly a dozen illustrations for The Lord of the Rings in 1968. Although Tolkien wasn’t particularly eager to find an illustrator for his magnum opus, he was very pleased by Fairburn’s illustrations, calling them “splendid.” Despite his satisfaction with the artist’s work, Tolkien was never able to work out an edition featuring her illustrations. Other notable illustrators of the period include Margrethe II, Crown Princess of Denmark, as well as art historian Cor Blok.  Figure 5 Jimmy Cauty 's popular 1976 poster would go on to become a national sensation. Figure 5 Jimmy Cauty 's popular 1976 poster would go on to become a national sensation. By the early 1970s, Tolkien’s work had permeated pop culture around the world. With his passing in 1973, many artists jumped at the opportunity to illustrate Tolkien’s master works. While not a direct adaptation, the popular role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons (1974) was heavily influenced by Tolkien’s creations, featuring Elves, Dwarves, Halflings, Orcs, Trolls, and even Ents. One notable artist was a young Jimmy Cauty, who drew a popular Lord of the Rings poster in 1976 that would go on to become a national sensation. That same year saw the release of the officially licensed Ballantine calendar, featuring art by the legendary Greg and Tim Hildebrandt. They went on to create dozens of paintings for the 1977 and 1978 calendars as well. The paintings of the Brothers Hildebrandt were artistic masterpieces that offered a defining visual interpretation of Tolkien for a generation. They meticulously set up their lighting equipment, dressed up in various costumes, and even hired friends and neighbors to pose for the scenes they visualized in their minds. Using their Polaroid snapshots, they would then compose a blueprint for how they wanted to approach each painting. In November of 1977, Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass released The Hobbit (1977), an animated musical television special. Known for their work with stop motion animation, the duo behind Rankin/Bass Productions crafted beautiful animated film that harkened back to the illustrations of Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac. Adapted for the screen by Romeo Muller, the filmmakers were adamant about not adding anything to the story that wasn’t in the original. It cost a reported $3 million to produce. The story’s titular character, Bilbo Baggins, is voiced by Orson Bean, while notable Hollywood legend, John Huston, provided the voice for Gandalf. The film featured a variety of musical numbers that would resonate with a younger audience. Jules Bass primarily adapted Tolkien’s original lyrics, which featured prominently in the book. The main theme of the film, “The Greatest Adventure,” was composed by Maury Laws and sung by Glenn Yarbrough. The animation was created by Topcraft, a Japanese animation studio that would eventually evolve into Studio Ghibli, under Hayao Miyazaki. While Topcraft produced the animation, however, all of the concept artwork was created under the direction of Arthur Rankin. Before the film ever aired on NBC, Rankin/Bass Productions were already in talks for a sequel. Meanwhile, filmmaker Ralph Bakshi was busy at work producing his own animated feature film of The Lord of the Rings for United Artists. Bakshi envisioned his story spread over two feature-length films. Despite his efforts, the producers eventually decided to do only one film, which resulted in Bakshi’s film only covering the events of The Fellowship of the Ring and the first half of The Two Towers. The film is notable for its extensive use of rotoscoping, a cinematic technique in which scenes are first shot in live-action, then traced over onto animation cels. It ended up using a combination of both rotoscoped live-action footage and traditional cel animation. With a screenplay by Peter S. Beagle, the film featured the voices of John Hurt, William Squire, Michael Graham Cox, and Anthony Daniels. Although it was a financial success, the film received mixed reactions from critics at the time, crushing hopes for any sequel to follow. After the sequel to Bakshi’s film was canceled by United Artists, Rankin/Bass proceeded with their own sequel, bringing back most of the animation team and voice cast. Taking elements from The Return of the King, Rankin/Bass intended on concluding the story of the Ring of Power. Considering the limited screen time and budget, the filmmakers were unable to provide adequate continuity for the missing segments, however, instead relying on a framing device in which the film begins and ends with Bilbo’s stay at Rivendell, similar to the first film. They also used a musical montage to recap portions of the story that were gleaned over. The television special aired on May 11, 1980 on ABC. In the absence of an official sequel to Bakshi’s film, the three animated productions came to be loosely marketed as a Tolkien trilogy. History became legend. Legend became myth. And for nearly two decades, the ring passed out of all knowledge (or so it seemed). Aside from a few fantasy films in the early 1980s like Excalibur (1981), Dragonslayer (1981), and Conan the Barbarian (1982), a substantial high fantasy presence was largely missing from the industry. In the mid-1990s, Peter Jackson and his partner Fran Walsh decided to embark on a grand adventure of bringing The Lord of the Rings to life on the silver screen. Produced entirely in New Zealand, the films ended up taking nearly 7 years of production time. The filmmakers brought on legendary artists Alan Lee and John Howe to design all of the concept artwork that would inform the films, including landscapes, architecture, costumes, props, and every other design element one can think of. Debuting in December, The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) came to theaters first, followed by The Two Towers (2002), and finally The Return of the King (2003). With a staggering budget of over $281 million, the films more than recouped their costs by generating nearly $3 billion at the box office worldwide. Collectively they racked up 17 Academy Awards, with the final film nabbing the Best Picture and Best Director awards to worldwide acclaim. Nearly a decade later, Peter Jackson and his team would return to film the Hobbit trilogy as well. Utilizing much of the same production team, including Alan Lee and John Howe as concept artists and designers, the films managed to maintain an amazing level of consistency across the now six-part saga. An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), and The Battle of the Five Armies (2014) were a box office smash hit, just like their predecessors, conjuring a healthy $3 billion worldwide. Despite some initial reservations regarding the spreading of the shorter story over three pictures, the films have stood the test of time and remain a remarkable achievement in cinematic history. The evolution of Tolkien adaptations through the years offers a stunning look at how different artists can contribute to a wide-range of unique interpretations of Middle-earth. Tolkien’s legendarium remains a rich body of work, waiting to be excavated by the next adventurous filmmaker who dares to step forth. With Amazon’s Middle-earth production on the horizon, the road goes ever on..

1 Comment

Son Of Dread

3/13/2023 02:13:20 pm

These are some really good street art.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMohammad Osman is an Artist, Writer, & Cultural Historian. ArchivesCategories |

- Home

-

Articles

-

Film

>

- Dark Side of the Screen: The Art of Film Noir

- Gothic Romance: The Art of the Macabre

- Perchance to Dream: The Art of Dark Deco

- The Road Goes Ever On: The Art of Middle-Earth

- There and Back Again: The Visual Poetry of Middle-earth

- King Kong: The Eighth Wonder of the World

- It's Alive: Universal Classic Monsters

- It Came from Beyond: Invasion of the Sci-Fi Films

- Creatures of Habit: Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

- Myth and Magic: The Art of Comic Book Films

- Arabian Nights: Sinbad's Adventures

- Music >

- Games >

- History >

-

Film

>

- Artwork

- Community

- About

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed